Truth, as the old saying goes, is stranger than fiction. It is also on occasion harder to believe. Fiction has the advantage of the internal logic of the story. Truth has to actually be true, even if that truth is very carefully hidden behind convenient lies. Our dear Edgar, idly explored this idea in his satirical sequel to ‘A Thousand and one Arabian Nights.’

In the unlikely event your not aware of the original, A Thousand and one Arabian Nights is a famous collection of Middle Eastern folktales and stories. It’s history is extremely complicated but it certainly dates back to the 10th century and probably in some form several centuries earlier. It is occasionally referred to as the Arabian Cannon, though it is perhaps more rightly considered Persian rather than Arabian for the most part.

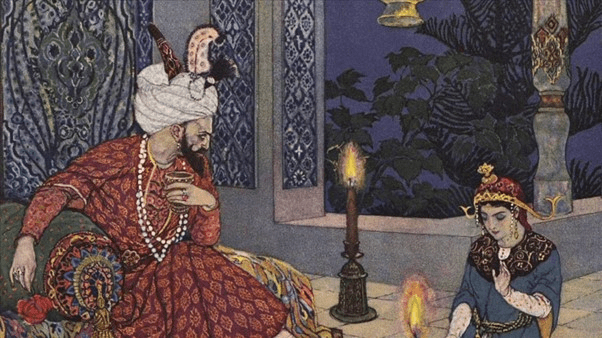

The framework of the collection is the conceit that these stories are told by Scheherazade the beautiful and wise Viziers daughter to her husband the king. The king, Sharryar, has been married before, and was greatly in love with his first wife, before he discovered she was inviting others to her bed and had her executed. In his anger he took to marrying a new virgin every day, sleeping with them on the weding night, then strangling them when the cock crowed each morning.

This has gone on a while…

Eventually when the Vizier can find no more virgins to wed to the king, virginity having lost much of its appeal among the ladies of the city, Scheherazade volunteers to wed the murderous king, but does so with a plan, she is going to tell him stories, but carefully make sure she doesn’t finish any story just before the cock crows each morn, and this she does, for a thousand and one nights. Until the king has fallen in love with her and no longer desires to strangle his new wife…

The thousand and one stories told by Scheherazade have origins from Egypt to India but are now considered to be the tales of the Arabian cannon, among the most famous among them being the stories of Aladdin, Ali Baba and of course Sinbad the sailor. There are many others and the collection has been added to and redacted at various times in its thousand year history. Stories by their nature fall in and out of vogue, but just about every type of story and genre imaginable is within the cannon, many of them utterly fantastical in nature.

Which brings us to our Dear Edgar and ‘The Thousand-and-Second Tale of Scheherazade’ in which Scheherazade tells one final story, and pushes her luck somewhat for the King doesn’t believe almost any of it. Scheherazade final tale is of the eighth and final voyage of Sinbad and describes all the strange things he discovers along the way, each more unlikely than the last. Such as this description of one of the strange things Sinbad encounters on his journey.

This terrible fowl had no head that we could perceive, but was fashioned entirely of belly, which was of a prodigious fatness and roundness, of a soft-looking substance, smooth, shining and striped with various colors. … in the interior of which we distinctly saw human beings … and then let fall upon our heads a heavy sack which proved to be filled with sand!

The king doesn’t believe any of this, but in actuality what Sinbad is describing here is a hot air balloon. Then there is this one…

a man out of brass and wood, and leather … with such ingenuity that he would have beaten at chess, all the race of mankind

Again the king believes this a complete fabrication, but it is in essence a description of ‘the Turk automaton’ and these two examples are not alone. Almost every miraculous and unlikely thing Sinbad encounters is a description of something real if odd discovered or constructed in Poe’s own time. Such as the Babbage computer, or the understanding of how coral is formed, or the extensive caves systems in Kentucky.

Each new oddity in Sinbad’s is found by the king to be increasingly far fetched, ridiculous and he becomes increasingly irate, if not insult, by them. Meanwhile Scheherazade isn’t paying quite enough attention to her husbands displeasure.

She also finishes her tale just as the cock crows…

The king then precedes to exhibit a rather unfortunate literary critique, and well, goes back to old ways.

This whole story, which is a story about a story told within a story about a woman famous for telling stories, relies on one very simple conceit. Everything can be fantastical if you tell it the right way. But to get the joke you need to know the references being made, most of which depend on you having an 1840’s understanding of the world.

This is a very clever story but to get the most out of it you need to understand each of the refences many of which are a tad oblique. On first reading the fantastical things Scheherazade describes do just seem ridiculous, it is only when you know what Poe is doing that they becomes clever and interesting. Much of the story just goes over the readers head, because that conceit is too well disguised. If you have to go and read an explanation of each of the refences to get the jokes then they are not actually funny. Take the enormous headless fowl above, in retrospect that is a brilliantly funny description of a hot air balloon, but I would be prepared to bet you did not realize that till I explained what it was. I certainly didn’t until I did some research on the story after I read it the first time. It was a lot funnier on the second read through…

And there is the crux of the problem with this story…

THREE RAVENS THAT HUNG ABOUT LONG ENOUGH FOR THE JOKE TO BE EXPLAINED

Should you read it: Well, yes, knowing that the jokes are there you should., its is very clever and a little funny in of itself.

Blaggers fact: The only part of Scheherazade final tale that the king believes to be true when Sinbad tells us that he discovers “the earth being upheld by a cow of a blue color, having horns four hundred in number” which is of course the only part of the tale not based on something real.

The cow isn’t blue, that’s ridiculous.