Sir William Nettleton VII, was once arrested for ‘lewd behaviour involving an elephant’ in his short stay in what was at the time refereed to as Eastern India, later became Burma and is now Myanmar one of only three nations in the world that still used British Imperial measurements for preference. None of which are Britain. Sir William was ejected from the state, and later died somewhere in the south china sea, of a previously unknown sexually transmitted disease called ‘trunk rot’ . No one is sure what happened to the elephant, though rumours it had to be put down persist.

The current Willian Nettleton who writes as Will Nett because he thinks it makes him sound cooler, hipper, but mostly to distance himself from the vast array of previous William Nettleton’s in the family line. Most of which have been a tad disreputable, and almost all entirely fictional…

Occasionally he send me guest blog posts, because he can’t be bothered to start his own blog. They are generally entertaining so I make up another distantly related Nettleton and put them out. They tend to be a mix bunch but well received, as Will is a tad elliptic at the best of times but seldom less than engaging.

This time he is wandering across my own wheel house to an extent with a post about Jules Verne, inspired by a visit to the authors birthplace, Nantes. But that’s enough form me, what follows is pure Will Nett, and also contains an elephant, consider that fair warning…

Verne : by Will Nett

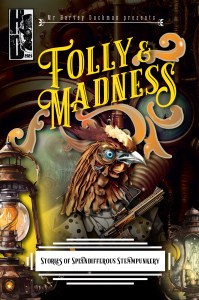

Few authors have left their mark on literature as indelibly as Nantes’ most famous son, Jules Verne, but it is the impression left upon him, as a child, as he sat in his boarding school classroom at rue de Bouffay, that occupies me now. I consider this as I sit outside l’Épicerie de Ginette, the restaurant that was once Verne’s school building. It was here, 186 years ago that Verne’s teacher told him that her husband had not yet returned from a Naval crusade he’d undertaken during the Napoleonic wars, but she fully expected his imminent return, all those years later once he grew tired of sunning himself on some desert island. The theme of this unconfirmed tale permeated Verne’s work and eventually led to one of the most remarkable periods of work in the life of any writer. In the space of less than a decade he published Journey to the Centre of the Earth, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, and, perhaps most famously of all, Around the World in 80 Days. These form part of a broader collection of lesser-known works from the Voyages Extraordinaires series that includes Mysterious Island and Master of the World. The series effectively created the modern template for adventure fiction that has influenced as a diverse a group of contemporaries as Hergé, the Beatles and Jacques Cousteau, and is the nascent steampunk springboard that permeates many a present-day fantasy novel.

Even Verne’s minor titles conjure up wonderment; Keraban the Inflexible; Off on a Comet; The Archipelago on Fire. It’s difficult to overestimate his contribution to the canon, but the little museum named for him, that sits high over the city on rue de l’Hermitage, appropriately enough beside the planetarium, doesn’t do his influence justice.

The inspiration for his most famous character, Phileas Fogg, is unknown but it is this writer’s conviction that he was a well-thought-out pop at the Establishment. One of the most recognisable travelers in fiction, Fogg was anything but a good nomad. He was in fact the antithesis of travel. A pompous braggart and Reform Club member who was too entitled to even cook for himself, Fogg famously rushed through towns and cities without so much as a cursory acknowledgment of his surroundings, in order that he collect on his famous bet of £20,000. The modern touristic equivalent would be a ‘foreign muck’ avoiding Daily Mail reader in Union flag underpants sunburnt to within an inch of his life and powered entirely by his own inflated sense of entitlement.

Fogg was facilitated in his hubristic endeavor by his put-upon manservant, Passepartout. I fancy that even though he represented many a bourgeois Frenchman of the time, Verne made him English to distance him from his homeland. It is Passepartout, former gymnast and ex-fireman who does the dirty work and gets the job done. His nationality? French, ironically, as the French are the least servile people you could ever meet, and the ones that are- I’m thinking of waiters like the one now collecting the remnants of a late breakfast from my table looking absolutely appalled that I’ve ordered a croissant after 10am in the morning- affect an air of inflated superiority so great that you can do nothing more than admire it.

In his hometown, Verne is better represented by the incredible phenomenon that is the Machines of the Island of Nantes, a visceral realization of Verne’s imagination, brought to life by François Delarozière and Pierre Orefice in the form of giant mechanical versions of a whole array of steampunkian creatures and creations. The centerpiece of the collection is the magisterial Great Elephant, or Sultan’s Elephant, after its basis on Delaroziere’s creation for the Royal de Luxe world tour. The forty-six-tonne beast- topping out at fifty when carrying its full capacity of amazed tourists- is concocted from metal and tulip wood and operated by a pilot in a cabin behind the water-spraying trunk. I feel like I’m tripping just looking at it.

I am tripping, but that’s another story.

A supporting ground crew of marionette operators busy themselves around the Underwater Carousel, an equally impressive contraption that occupies the carpark beside the Machines workshop, L’inusable. Invincible. Nothing conjures up the same sense of magic and intrepidation of the undersea world created by Verne like the carousel, bedecked as it is with serpents, bobbing trawlersand bronze bird-powered airships. The only thing missing is the sea mist on your face. The contraption clatters and farts like all the best Victorian automata as it twirls on the banks of the Loire, the river that first convinced Verne he could create these wonderful worlds. Children ride giant seahorses pursued by a giant grouper fish decked out like an early wooden submarine prototype. The red velvet curtains, tied back today, add to the stage show grandeur of the whole apparatus; beneath the main deck, l’abysse and its piranhas, cosmic langoustines and astro crabs. The elephant is scheduled for an afternoon stroll later so I occupy myself in the meantime with a walk around the industrial wonder that is the Machines’ workshop. A peek behind the curtain you might call it, where light is let in on magic as welders, fitters and angle-grinders work in tandem with design students and artists. I enter via a greenhouse that’s home to mechanical dragonflies and brass and bronze bees, poking out from beneath the real fauna as I follow the designated path through the exhibits. Eventually I’m greeted with a demonstration of a giant spider, all eight legs flailing independently at flying ants hung from the ceiling; nature recreated in steel and paint. Tourists armed with cameras duck and recoil as the operator playfully stalks them. The infectious amazement is childlike. A staircase leads to a balcony that overlooks the workshop, clear from its design that some parts of the projects are top secret, to obtain maximum effect when eventually unveiled to the public. Occasional spark-accompanied squawks spit from the angle grinders as they carve out wings, skulls, and various other avian automata. It’s a long way from the Industrial Revolution but it is there, in Verne’s time, that it has its roots, this culmination of art, literature and scientific engineering.