“Why would I eat your fingers?”

Folktales are ever a wonderous resource for a writer, for they tell us many things about stories we often forget. Things like ending do not need to be happy, the good and the virtuous don’t always win, and the forest is dark, old and full of terrors. Most importantly the remind us the soul of a good story is in the telling.

Folktales are not a written form of story telling, at least they were not in their original form. No one wrote the down, no one person invented them. Folktales grew on the tongues of those who told them, and grew again and again with each retelling. Folktales are in effect Chinese whispers across the generations, they change each time they are told. Twist this way and that. The origins of one tale bleed into another.

Bleed is the right analogy here, because folktales are alive and full of blood. The blood of a culture and a people. But they bleed into each other, they move around, and the stories change to reflect their surroundings, the country, and the people.

Folktales also tend to be full of blood.

But then they are campfire tales, fireside tales, tales to inspire fear on a dark night, and tales of warning. Tales told to children to keep them from wandering into the forest. Which of course they don’t because if you tell a child to fear the forest they are going to take that as a challenge. They are also tales that warn of devils and ghost and the price of straying from the church, because priests have never been above telling the odd folktale either.

Naturally, the majority of folktales in which my own soul is seeped are the folktales of Northern England as that’s from where I hail. Tales of the moorlands, and the tempestuous Yorkshire coast. Tales of huge black dogs. White ladies. Not a few pirates. Haunted castles and haunted hovels. The terrors of the sea, and haunted graveyards. And one or two witches. Most notably of course Mother Shipton the old witch who was born in a cave in Knaresborough where even after she died anything left there turned to stone.

This is of course entirely true… Anything left in the cave does indeed turn to stone Mother Shipton’s cave* is reputedly England’s oldest tourist trap, as the owners of the land have sold tickets to see the cave where England’s ‘most famous protheses and witch once lived and the dark magic she left that that still petrifies anything left in her home’ for the last 400 years or so.

Acctually this is because the extremely high mineral content of water dripping through the lime stone will coat anything with deposits that in a short time form an out shell of stone. But lets not let science get in the way of a good story…

Mother Shipton also has a moth named after her. May we all be so blessed…

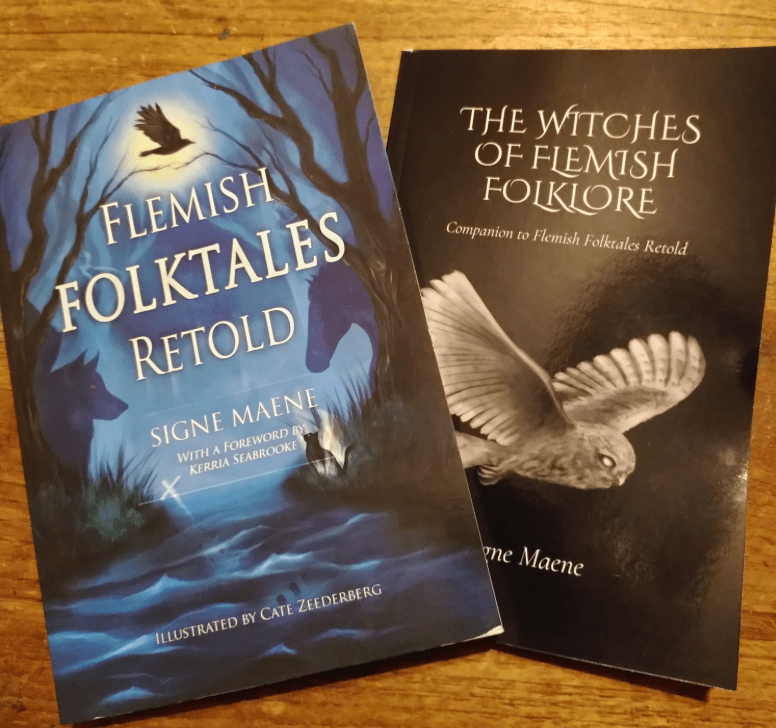

But not to get side tracked… back to that opening quote, and the ‘Terrifying Joy from the Forests of Flanders’. The quote about eating fingers is from the very first line of the very first story in Signe Maene’s wonderful book, Flemish Folktales Retold. So lets just say it gets off to a great start.

Divided into sections, Signe, as the title suggests, retells the folktales of the Flanders region of northern Belgium. A region where ancient forests used to meet the sea. A region rich in tales of witches, shapeshifters, ghosts and lost souls. Lots of witches… As we are told more than once in the End Notes of each section, around half of all Flemish folk tales involve witchcraft. Shape shifting witches fond of taking on the form of cats, owls and magpies, and in one particular case, a toad…

The End Notes for each section are fascinating as they add perspective and academic rigor to the collected sections. Some of the tales Signe has crafted are combinations of different folktales that lend themself to a single tale. Folktales by there nature change and twist in the telling, there are always different telling’s of similar tales. Signe takes this premise and masterfully weaves stories together.

And, like all folk tales they are stories with a dark edge, but in the case of these stories oft told from the perspective of the witch, the ghost, or the monster. The tale behind the tale. The sympathy lays often with the witch, and so it should. After all they cursed the village for a reason, oft reasons beyond pure malice, but in response to malice done on to them. This sets these tales apart from a simple collection of folktales. These are dark from the perspective of the darkness. Haunting from the perspective of the haunt.

Terrifying joys, and glimpses into Europe’s collective cultural past. For while these are all Flemish tales, they are tales that are echoed throughout Europe. Which is only natural, as travels tell tales of their homelands and those tales get retold and made anew. A such this book is tales of the kind told around the camp fire, on the edge of the woods, with twilight all around. Told to frighten, and to warn. The woods are dark, the wise do not wander there.

But who wants to be wise…

The book is also quite quite beautiful. Aside Signe’s word there are black and white illustrations by Cate Zeederberg which are just beautiful. A dark haunting beauty perfectly complimenting the prose, which hopefully Cate will not mind me reproducing a snippet of here, just as a taste, because you can not talk about this book without talking about both schools of art within its covers.

If you have an interest in folklore, you should read this book. If you don’t have an interest in folklore (why not?) you should read this book. Afterwards you will. It is available on kindle but I urge you to buy the paperback, as you will return to it more than once, and frankly it is a beautiful book with beautiful dark sinister art that you need to see on paper…

I am also currently reading the companion book, ‘The Witches of Flemish Folklore’ which is an equally fascinating non-fiction work about the folklore of the region. and of course witches.

*You can still visit England’s oldest tourist trap Mother Shipton’s cave, which remains in previous hands. For a while in the 80’s it was owned by irritating stage magician Paul Danial’s… Almost every school child in Yorkshire visits it at least once.